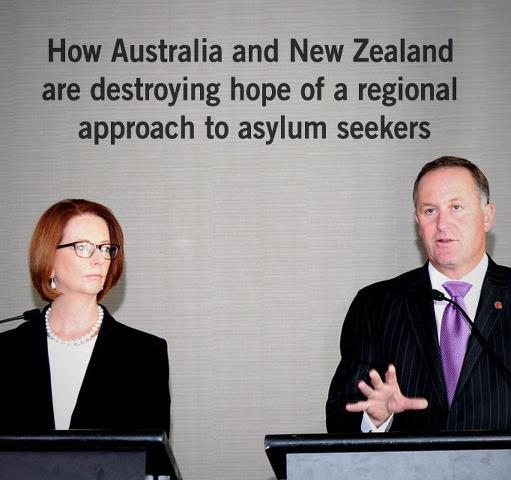

Last weekend the New Zealand government made a deal with Australia to take 150 asylum seekers held in Australian detention facilities. New Zealand accepts the fifth highest number (equal with Canada) of refugees per capita, but this move reduces the number of refugees selected through New Zealand’s quota of 750 by 150 (600 refugees a year compared with 50,000 in the United States and 20,000 in Australia). What’s even more alarming as Gordon Campbell notes, is the way in which this new deal conflates two very different mechanisms for refugee arrival.

There are two ways in which refugees are able to remain in New Zealand. The first is the quota category, which in New Zealand is presently 750 persons per annum. People are recommended by the UNHCR to Immigration New Zealand (INZ) for selection. The refugees who apply for resettlement in New Zealand must meet the definition of a refugee given below. The second resettlement category includes Convention Refugees, or Asylum Seekers. Asylum seekers most often arrive at Auckland International Airport and then need to go through an application process to be granted refugee status and be able to settle in New Zealand. A boat of asylum seekers has never reached New Zealand.

It is a right under the UN Refugee Convention to claim political asylum and there is no queue. A claim for asylum is carefully assessed and if there are grounds for political persecution, asylum has to be granted. It is a completely different procedure from the UN annual refugee quota of 750. The 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees is the key legal document, outlining the rights of refugees and the legal obligations of signatory states. Article 1 (2) of the United Nations’ 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees modifies Article 1 A (2) of the 1951 Convention to define a refugee as a person who:

owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such a fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

This definition only refers to people who have fled their country of origin and then sought sanctuary in a second country for protection.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is an international agency that provides protection for refugees, Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), asylum seekers, and stateless persons—it attempts to find long-term solutions for a number of the world’s refugees. There are three options: the first is voluntary repatriation; the second is local integration in the country of asylum; and in the third, the UNHCR works with eighteen countries with established or developing resettlement programmes to resettle refugees in a third country, including Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of America. Countries with emerging programmes are Benin, Brazil, Britain, Burkina Faso, Chile, Iceland, Ireland and Spain.

The earliest refugees to New Zealand arrived between 1870–1890 and included Danes, Russian Jews and French Huguenots. Subsequently, refugees from Nazism (1933–39), Poland (1944), Hungary (1956–58), ‘handicapped’ refugees (1959), Chinese (1962– 71), Russian Christians from China (1965), Asians from Uganda (1972–73), Chileans, Soviet Jews, Eastern Europeans, people from the Middle East, South-East Asia (Indo-Chinese), Somalia, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, Bosnia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Iran and the Sudan have resettled in New Zealand—over 40,000 refugees.

New Zealand only developed its quota programme in 1987. The development of a formal annual quota for refugees occurred concurrently with the Immigration Policy Review of 1986 and subsequent Immigration Act 1987. This legislation brought into being more diverse migrants to New Zealand. Whereas previously, migrants had been selected on the basis of country of origin (primarily European), the new legislation liberalised migration so that migrants entered New Zealand by way of a points system on the basis of skills. Other significant changes included the development of four migration categories—occupational, business, family, and humanitarian. The latter category represented refugee policies and saw the introduction of an annual quota for resettling refugees.

The Minister of Immigration and the Minister of Foreign Affairs set the composition of the refugee quota. This process takes into account the UNHCR’s international protection priorities, the needs of refugee communities settled in New Zealand, and the capabilities of New Zealand as a host country. The UNHCR refers refugee cases to Immigration New Zealand for consideration under the refugee quota. The refugees are then assessed by Immigration New Zealand, which makes a final decision on the refugees’ admission to New Zealand. The quota comprises up to six intakes a year of around 125 people each.

One of my concerns is that this move will impact on special categories within our NZ Refugee Quota Programme such as national, ethnic and religious groups, as well as special needs groups such as ‘handicapped’ refugees, long stayers in refugee camps, and refugee “boat people” rescued at sea (Tampa). In particular from these formal categories introduced in 1992:

- Protection (600 persons)—This category includes up to 300 places for family members, covering hgh-priority refugees needing protection from an emergency situation.

- Medical and/or disabled cases (75 persons)—Refugees with a medical condition or disability that cannot be treated in the country of asylum but can be treated in New Zealand. This special category “provides for the resettlement of refugees with medical, physical or social disabilities which place them outside the normal criteria for acceptance by resettlement countries” (Parsons, 2005).

- Women at risk (75 persons)—Women refugees (alone or with dependant children) at risk in a refugee camp, especially from sexual violence (75 persons). New Zealand, like Canada and Australia, has created a special category for resettling women at risk. The UNHCR definition for refugees in this category includes:

Women and girls who have protection problems particular to their gender…including expulsion, refoulement and other security threats, sexual violence, physical abuse, intimidation, torture, particular economic hardship or marginalization, lack of integration prospects, community hostility, and different forms of exploitation. Such problems and threats…may render some refugee women or girls particularly vulnerable. (UNHCR, 2002, p. 22).

In addition to the refugee quota, 300 places are made available per year for family members to be sponsored under the Refugee Family Support category who would otherwise be unable to qualify for residence under any other category of government residence policy. The government has recently made changes to the category, including expanding the definition of family member, to recognise a wider range of family structures. It also introduced a ballot system in 2002.

My other concern is that New Zealand should be doing more not less. For all the criticism of Australian policy, its annual refugee intake as a proportion of its population is still five times ours. Why not either increase our overall refugee quota to 900 so that it includes the number of people from Australia as this Dominion Post editorial suggests:

And this means that 150 other refugees, typically rotting in wretched camps near some of the ghastliest places on earth, will not be able to come to New Zealand.

Their places will be taken by those who were lucky enough to have become the responsibility of Australia. This isn’t really fair. Australia’s rejected refugees are not necessarily more deserving than the 150 who will miss out.A more compassionate approach would have been simply to increase the overall refugee quota by 150, bringing it to 900.

Race Relations Commissioner, Mr Joris de Bres supports this increase and advocates for refugees accepted from Australia to be subject to a bilateral agreement and distinguished from the humanitarian refugee quota:

The 150 places should be in addition to the annual quota. The quota is a separate arrangement, and the Government’s announcement could constitute an ongoing reduction in New Zealand’s humanitarian commitment to the UNHCR to accept up to 750 refugees in need of resettlement. The present 750 refugee quota includes specific groups including women at risk, disabled people and family linked cases. The announcement may diminish New Zealand humanitarian response to these vulnerable groups of refugees.For transparency, any refugees accepted from Australian detention camps should be subject to a bilateral agreement separate and distinct from the humanitarian refugee quota.

Another concern is whether in tone, language, media and treatment we are emulating a punitive and dehumanising Australian asylum seeker policy. Bryce Edwards in the National Business Review notes that:

we have effectively approved and given international legitimacy to an Australian policy that ‘is the outcome of squalid politics, beginning with John Howard’s demonising of the boat people and exaggerating their threat. The effectiveness of the scare tactics, also employed after Howard left the scene, forced Gillard to reopen the foreign detention centres – centres of human misery.

Photos received by Sarah Hanson-Young of the Manus Island Detention Centre, Nauru. from an article by Bianca Hall

Photos received by Sarah Hanson-Young of the Manus Island Detention Centre, Nauru. from an article by Bianca Hall

Brian Rudman in the Herald observes that John Key is embracing a particularly hellish vision:

Amnesty International’s refugee expert, Dr Graham Thom, after a visit to the Nauru camp in November, called the conditions “cruel, inhuman and degrading”, with 387 men cramped into five rows of leaking tents “suffering from physical and mental ailments – creating a climate of anguish as the repressively hot monsoon season begins”. Dr Thom said “the news that five years could be the wait time for these men under the Government’s ‘no advantage’ policy added insult to injury”, with one man attempting to take his life while the Amnesty group were visiting.

Even former MP’s have jumped in Aussie Malcolm in the Herald:

Australia and Australia alone stands out from the rest of the world with arguments about queue jumpers and all sorts of populist jargon that actually hides racism, and now New Zealand has joined Australia it’s a tragedy,” Mr Malcolm told Radio New Zealand…It couldn’t be a worse outcome.

Jan Logie of the Green party asked questions in parliament but interestingly enough there’s been silence from our Labour party as the National Business Review points out:

Yet opposition parties have been noticeably weak in their critiques of the policy, choosing to play it safe. A Labour-led government, David Shearer says, wouldn’t necessarily reverse the policy, and instead ‘Labour would discuss the policy with Australia’

I’m with Michael Timmins a New Zealand refugee lawyer when he suggests that New Zealand could play a positive role and improve protection in the region rather than “cosy[ing] up to Australia’s broken asylum system”. In his excellent article, he suggests engaging in regional co-operation and working with South East Asian countries so that they can properly process refugees. New Zealand is at a cross-roads, we can choose to punish groups of people who demonstrate incredible courage to leave horrendous circumstances or we can attempt to find some solutions that uphold people’s human rights and dignity.I know which I would prefer.