Exploring the role, benefits, challenges & potential of ethnic media in NZ .

Paper presented at the Ethnic Migrant Media Forum, Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. Also available as pdf from conference proceedings DeSouza keynote.

Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou katoa, it’s an honour to be invited to speak at this forum where we are gathered to talk about ethnic media and the possibilities it offers for our communities. I wish to acknowledge this magnificent whare whakairo (carved meeting house) ‘Ngākau Māhaki’, built and designed by Dr Lyonel Grant which I think is the most beautiful building in the entire world. Kia ora to matua Hare Paniora for the whaikōrero, whaea Lynda Toki for the karanga and this pōwhiri. I acknowledge Ngāti Whātua as mana whenua of Unitec and Te Noho Kotahitanga marae. I acknowledge the organisers of this forum, Unitec’s Department of Communication Studies and Niche Media & Ethnic Media Information NZ, in particular Associate Professor Evangelia Papoutsaki, Dr Elena Kolesova, Lisa Engledew and Dr Jocelyn Williams and all the participants gathered here today.

As a migrant to Aotearoa and now Australia, there are a few places that I call home. Tamaki makau rau and Unitec specifically would be one of those places. This whenua has been central to my own growth and development. I love these grounds, I walked them when I was a student nurse at Oakley hospital in 1986 and then worked in Building 1 or as it was known then Ward 12 at Carrington Psychiatric Hospital in 1987. I also worked here at Unitec as a nursing lecturer from 1998-2004. I have this beautiful Whaariki (woven mat) made from Harakeke (NZ Flax) grown, dyed and woven at Unitec that has accompanied me for over three house moves since I left Unitec and more recently across the Tasman.

It is this being at home that interests me as a migrant. Home is the safe space where I can be myself and where there are other people like me. It’s a place where I can be nurtured and supported, where I can thrive in my similarities and in my differences. Where I can see my norms and values reflected around me. I believe that the media can have a special place in helping us to see ourselves as woven through like this exquisite mat as belonging to something larger than ourselves. I believe that it can contribute to helping us feel at home, through it we can feel embraced and included, we can be part of a conversation that can see us in all our glory. However, too often it is also a site where if we are already marginalised, we can be further marginalised.

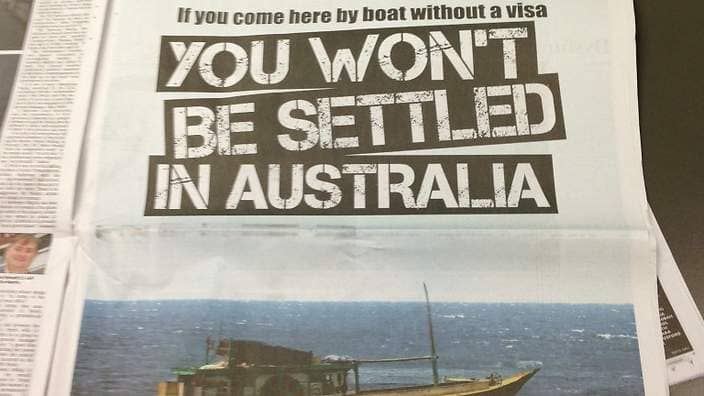

Advert in the Australian 2013

Today, I am going to briefly talk about the limitations of mainstream media, review some key functions of ethnic media and conclude with some challenges and opportunities for ethnic media. As you’ll see from my bio, I co-founded the Aotearoa Ethnic Network, an email list and journal in 2006 to provide a communication channel for the growing number of people in the “ethnic” category. I’ve been passionately interested in the role of media practices in intercultural relations in health, and also on the relations between settlers, migrants and indigenous peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand. I have been actively involved in ethnic community issues, governance, research and education in New Zealand and Australia.

This hui is timely, given discussions about: biculturalism and multiculturalism; the Maori media renaissance, the growth of Pacific and Asian owned or run media including radio, newspapers, online media; television, web based news services; the underrepresentation of Maori, Pacific and Ethnic in media and journalism; the growth of blogs through early 2000s and the growth in social media (FB, Twitter) in the last decade. It’s also part of a longer conversation, I’m thinking about the forum we had in 2005 organised by the Auckland City Council and Human Rights Commission after the Danish cartoon fiasco, where I talked about the role of media in terms of “fixing” difference or supporting complexity; the role of media in making society more cohesive or divisive or exclusive and the relevance of New Zealand media relevant in the context of growing diasporic media. In that forum I suggested that there was a need for: ethnic media but also adequate representation in mainstream media; the showing of complex multicultural relationships not just ethnic enclaves and ways for people of ethnic backgrounds to be included in national and international conversations. Me and others have also taken mainstream media to task over representations of Asians (Asian Angst story by Debra Coddington);Paul Brennan’s Islamophobic comments on National Radio and Paul Henry’s comments about then Governor General Anand Satyanand. An editorial in the AEN Journal also examines the role of mainstream media in inter-cultural exchange and promoting inter-cultural awareness and understanding. I also challenged media representations of Maori and Pacific people as evidenced in cartoons by Al Nisbet, which were printed in New Zealand media. More recently, I’ve written with colleagues Nairn, Moewaka Barnes, Rankine, Borell, and McCreanor about the role and implications of media news practices for those committed to social justice and health equity.

Let me start by introducing a fairly binary definition of ethnic media that I am going to use as referring to media created for/by immigrants, ethnic and language minority groups and indigenous groups (Matsaganis et al., 2011). In contrast, media that produces content about and for the mainstream is known as the mainstream media. However, as most of you will know there’s a lot of blurriness and consumers consume both. I also want to preface this talk by introducing two key words which I am going to use as a lens for this keynote. I believe that these lenses are more important than ever in an era where critique is becoming censured for those in academia and in the context of corporate governance of media. Foucault’s notion of critique which is

“..a critique is not a matter of saying that things are not right as they are. It is a matter of pointing out on what kinds of assumptions, what kinds of familiar, unchallenged, unconsidered modes of thought the practices we accept rest” (Foucault, 1988, p.154).

and Stuart Hall’s definition of ideology:

Ideology: “The mental frameworks – the language, concepts, categories, imagery of thought and system of representation – which different classes and social groups deploy in order to make sense of, define, figure out and render intelligible the way society works” (Hall, 1996 p. 26).

It’s in the spirit of critique that I want to talk about the mainstream media’s role in co-option and converting audiences into seeing “like the media”. As Augie Fleras observes, media messages reflect and advance dominant discourses which are expertly concealed and normalised so as to appear without bias or perspective. The integrative role of mainstream media reflects and amplifies the concerns of particular groupings of power so that attention is drawn to norms and values that are considered appropriate within society. In this way attitudes are created and reinforced, opinions and understandings are managed and cultures are constructed and reinvented. The headline below shows the ways in which language is used to create an “other”, the picture out of focus, the beard a stand in for evil and fear, a threat to national security.

Sponsor a jihad

Thus mainstream media’s main function becomes commercial, selling by pooling groups together for the purposes of advertising and marketing and in so doing must appeal to a large audience. It can’t be too controversial (unless it’s also supporting larger official agendas such as guarding against the insider Islamic threat or deterring the hordes of maritime arrivals through forcibly turning back the boats) and it cannot segment its audiences with any kind of nuance. I think this meme floating around Facebook captures this idea of communicating some kind of national identity and values well.

Consequently social media, the internet and ethnic media are seen as able to service more specific audiences. In the case of social media, there’s some great opportunities for connecting beyond the nation state:

As the internet surpasses the nation-state limitations and usually the legislative limitations that bind other media, it opens up new possibilities for sustaining diasporic community relations and even for reinventing diasporic relations and communication that were either weak or non- existent in the past (Georgiou 2002: 25).

Moving on to ethnic media, I see several functions or imperatives loosely using the typology by Viswanath & Arora (2000): Ethnic media as form of cultural transmission, community booster, sentinel, assimilator, information provider and one lesser mentioned in the literature, as having a professional development function.

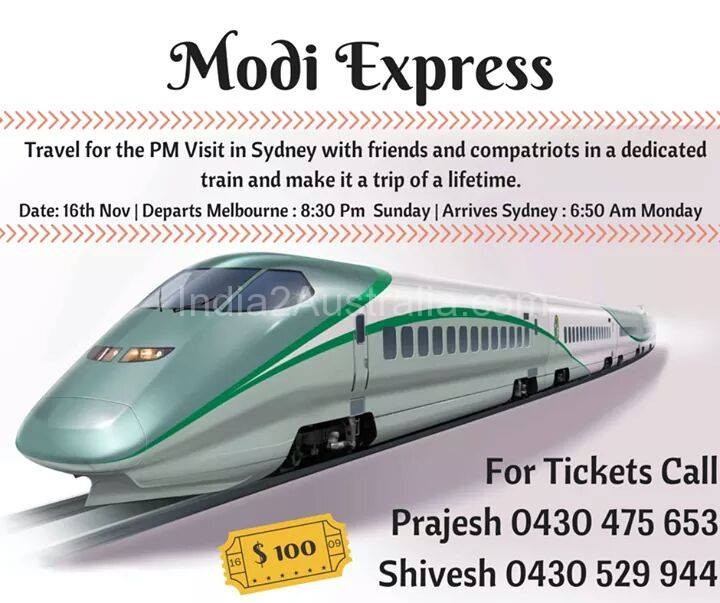

The most obvious role of ethnic media is to provide information for the community, events both local and from the homeland are paid attention to. In the break I was talking to a journalist from Radio Torana who is flying to Brisbane for the G20 summit and to cover Modi’s visit to Australia. Through him I found out about the Modi express. For the first time ever, a train service is running under the name of an Indian Prime Minister from Melbourne to Sydney carrying some 200 passengers who are planning to attend Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s public address in Sydney during his visit to Australia, the first by an Indian premier in 28 years (Rajiv Gandhi was the last, he met with Bob Hawke in 1986). The organisers have arranged for music and dance troupes to entertain the passengers along with free Gujarati specialties like ‘Modi Dhokla’ and ‘Modi Fafda’ (Fafda is crunchy snack made from chick pea flour and served with hot fried chillis or chutney and Dhokla is snack item made from a fermented batter of chickpeas accompanied with green chutney and tamarind chutney).

Photo from India2Australia.com

In its role as cultural transmitter, it has a distributive function to publish or broadcast information that is important to the ethnic community, so information about events and celebrations comes to the fore. This in turn sustains and fosters a sense of belonging to an imagined community, that feels coherent, united and connected to a homeland. However, rarely in that role does it also act as a critic of community institutions or powerful groups within that community.

A second role of ethnic media is as a community booster. In this role the media presents the community as doing well, being successful and achieving. The communities served by the media expect that a positive image is reflected both to its own members and outside the community. Typically close links are fostered between local reporters and editors and the community elite. Stories consist of human interest features, profiles of successful members, particularly those that are volunteers or contribute. There many be a reluctance to feature more radical or critical voices or critical stories as these many adversely affect the community image and the commercial imperative.

A third role is the ethnic media as a sentinel or watch dog. There’s very little about this in the literature but in fulfilling this role, the ethnic media produce stories on issues that could affect the rights of communities, crime against immigrants and so on.

A more common function is that of assimilation, where ethnic media play a part in assisting their community members to be more successful; through learning the ropes of the system. Ethnic media coverage then focuses on the role of the community in local politics and fostering positive relations and feelings between that of the ethnic group’s homeland and adopted country.

Another crucial function which is rarely articulated in this literature, but has been pivotal to my development is that of the ethnic media as space for professional development. Through engagement in ethnic media, members of ethnic communities develop transferrable skills and the capacity to write, broadcast and present. This one is very personally relevant. Through writing for the Migrant News and Global Indian, I refined my writing skills. Through talking on ethnic radio stations like Samut Sari and Planet FM I developed and refined my own capacity to articulate thoughts and ideas. Being featured in stories on Asia Downunder I realised my own ability to speak on television. These opportunities led to developing the confidence to develop my own online journal, the Aotearoa Ethnic Network Journal and write peer reviewed publications and feature on commercial radio and television. This would never have happened without the support of those ethnic media pioneers. I acknowledge them all.

However, ethnic media is on rapidly shifting terrain. Increasingly consumers are negotiating the availability of media from their place of origin via the internet. Ethnic media are having to consider their roles and business models in the context of neoliberalism and the withdrawal of the state from cultural funding.

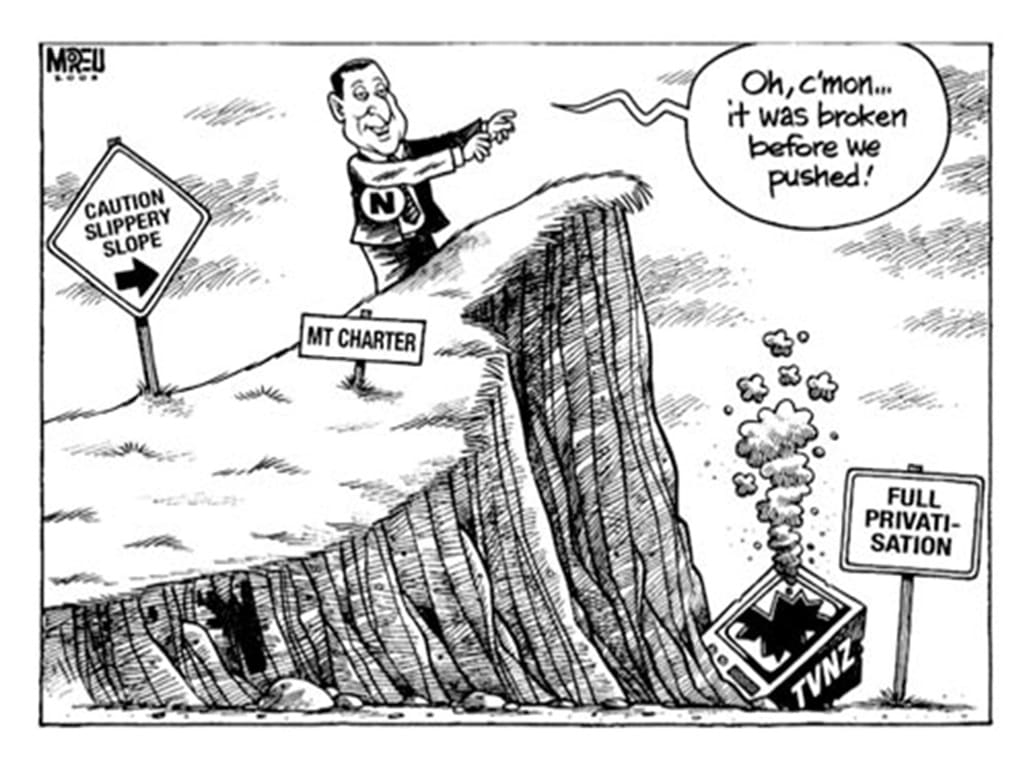

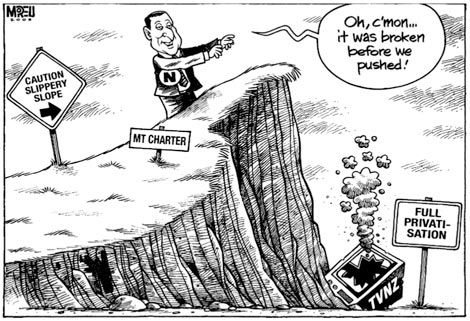

The end of the charter. Picture via Against the Current

Recently Television New Zealand the public service broadcaster announced that it intended to outsource production of Māori programmes (Marae, Waka Huia) and Pacific (Fresh and Tagata Pasifika) programmes. A depressing move given the unrelenting negative representations of people in these communities who are socially and culturally marginalised in New Zealand mainstream media (see my blog post on how blame for the disparities in health is attributed to individuals and communities rather than neoliberal and austerity policies). This very manoeuvre was used to outsource Asia Downunder a programme which ran from 1994-2011 for Asians in New Zealand and featured the activities of Asians in New Zealand and New Zealand Asians abroad gutted Asian institutional knowledge and capacity within TVNZ when it was replaced with Neighbourhood. Asia Downunder was a casualty of the loss of the Television New Zealand Charter which was introduced in 2003 by the Labour government and removed in 2011 by the National government on the basis that meeting its public service obligations were a barrier to its commercial obligations. The Charter encouraged TVNZ to show programmes that reflect New Zealand’s identity and provided funding. You can read more about its history and gestation and what has been lost in The End of an Error? The Death of the TVNZ Charter and its implications for broadcasting policy in New Zealand by Peter A. Thompson, Senior Lecturer, Media Studies Programme, Victoria University of Wellington.

In this context, I end with several questions. Given that ethnic media institutions help their audiences to reimage or sustain themselves and their place in the cultural and socio-political milieu of their new home (Gentles-Peart):

- What is the relationship between ethnic media and the ‘mainstream ideological apparatus of power? (Shi, 2009: 599)

- What is the relevance of ethnic media in terms of the next generation?

- What is the relationship between ethnic media and indigenous media?

- How do ethnic media import or reinforce or critique the power structures of immigrants’ homelands including gender, class and sexuality?

- Are there opportunities for ethnic media to lobby and advocate for their communities?

- What opportunities and possibilities are available for inter-ethnic media work?

I look forward to summing up the korero at the end of our forum, to report back to the roopu about the strands we’ve woven together and to enjoying the robust and dynamic discussions that I know are going to happen today. No reira me mihi nui kia koutou katoa ano, tena koutou tena koutou, tena ra koutou katoa.

Update: 12th March 2017: the curated conference proceedings of the Ethnic Migrant Media Forum are now available. Edited by Evangelia Papoutsaki & Elena Kolesova with Laura Stephenson.