Cultural safety in health is the radical idea that people who use health services should be treated with competence, care and respect, so that their dignity and sovereignty are maintained, and not compromised by the system of health care. Both an ethical framework for negotiating relationship and an outcome of care, cultural safety rests on transforming power relations and disrupting universal factory models of care premised on an ideal implicit service user, who is typically able bodied, straight, cis gendered, white and middle class. Cultural safety provides a counter to the reductionism and individualism of episodic care in medicine, to demand that the health of recipients of care whether as individuals, families or communities is holistic and seen in the context of historical and geographical determinants.

There’s an extensive bibliography on the genesis of cultural safety, but briefly it’s a concept developed in Aotearoa, New Zealand by Māori nurses that’s travelled to other white settler nations like Canada, and contexts including the arts. It is a really exciting time for the concept of cultural safety in Australia as it gains momentum among Indigenous health advocates but more broadly in health contexts, challenging inter-changeably used terms like cultural awareness and cultural competence. Mark Lock has beautifully outlined developments in his article on How to Embed Cultural Safety in Healthcare Governance – Better Boards. These developments include:

- The Medical Board of Australia, public consultation on a draft revised code of conduct including a revised section on culturally safe and sensitive practice with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (June 2018).

- The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia–care is ‘culturally safe and respectful’ (2018).

- The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Authority (AHPRA) committing to embedding cultural safety in the 15 national health practitioner boards (July 2018).

- The Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) Health Council public consultation on reforms of the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (July 2018).

- The National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards now contain six new actions for implementation in 2019, where achieving these actions means ‘provide culturally safe care’ for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (2019).

- $350,000 for Australian-first online cultural safety training course for nurses and midwives delivering care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (January 2019).

Recently, The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) asked for feedback on the definition of ‘cultural safety’ both from the public and specifically from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and organisations. The public consultation which closes next week (May 24th 2019) is led by the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Strategy Group (Strategy Group) and the National Health Leadership Forum (NHLF), with the aim being to develop a definition that can be embedded more broadly. This is the proposed definition they want feedback on

‘Cultural safety is the individual and institutional knowledge, skills, attitudes and competencies needed to deliver optimal health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait slander Peoples as determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families and communities.

I really recommend reading the incisive and comprehensive critique of AHPRA’s definition of cultural safety in Croakey. Dr Leonie Cox (Queensland University of Technology) and Associate Professor Odette Best (University of Southern Queensland) argue that changing the definition from Māori scholar Dr Irihapeti Merenia Ramsden’s critical work replaces a political imperative with an individualised, ethnographic and idealised version which places the burden for health system transformation to the consumer in the guise of partnership. Cox and Best (2019) observe:

Let us be clear, cultural safety is about the cultures of systems, professions and practitioners. It is about an ongoing individual and organisational self-reflective exercise. It addresses the impact that mainstream cultures, ways of doing business and social positions have on practice and on health outcomes for service users.

I am pleased to have been involved in related initiatives happening in Victoria. In November 2018 I was invited to speak at the Victorian Clinical Council meeting, an independent group, which provides leadership and independent advice to the Department of Health and Human Services and Safer Care Victoria (SCV) on how to make the health system safer. The council had chosen the theme of diversity and cultural safety. In my presentation, I provided an overview of cultural safety. I also suggested a shift in focus from the language of diversity, to one that addresses power and privilege using critical tools like intersectionality and cultural safety. I shared the five facts about cultural safety and encouraged the council to ask disruptive questions and explore alternative ideas and perspectives. You can read more hereCommunique meeting 4 2018 (PDF, 130.27 KB). You can see the recommendations which will be presented to SCV and the department Secretary to endorse and action.

In April 2019, I was invited to be a keynote at Safer Care Victoria’s first

Partnering in healthcare forum. The theme ‘Together is better’ is a reflection of a genuine commitment to ensure consumers are at the centre of care. Three hundred attendees attended the sold out event over two days to focus on how to best respond to the needs and expectations of consumers and deliver care that is person centred, equitable and caring. What impressed me ever so much is that Safer Care Victoria worked hard to support consumers to take part and over a hundred participants identified as having a consumer background. SCV have also developed a Partnering in healthcare framework. I have had a long interest in power relations in health and in examining how concepts like choice, partnership and empowerment can transfer responsibility to service users but without the access to infrastructure, resources and support. I loved David Gilbert’s presentation. David is a Consumer Director in the National Health Service, UK and he spoke about the role of consumers and patients and how the notion of ‘patient leadership’ in the UK is transforming roles, opportunities, and models of patient partnership. In a fabulous article in the BMJ, David says:

Meanwhile, I watch the failure of the engagement industry—reliant on child-parent feedback mechanisms and adolescent-parent institutional arrangements that pit representatives against professionals (or co-opt them) in tedious sub-sub-committees. And yields… not much to be honest. Everywhere I look, power is neutralised and buffered. We are patted on the head, told to play with broken toys rather than join in with the big boys. The passion and wisdom gained through suffering and resilience is not valued. This is a caricature, but I believe it largely represents recent reality.

I really appreciated what David said about what we call people who try to change the system rather than healing in peace. occupy what do we call idiots like me who, instead of just wanting to heal in peace, return to the NHS in a different guise?

There were so many other highlights at the Partnering Forum which gave me great heart. One of the standouts (and I know I should mention every single one) was by Clinical Lead and Facilitator for the Rounds, Associate Professor Leeroy William, Chief Experience Officer Anne Marie Hadley and Anjali Dhulia from the Schwartz Round team who provide palliative care at Monash Health. This team were highly commended in the Safer Care Victoria compassionate care award category for the ‘Rounds’ which are a structured forum for all clinical and non-clinical staff. It provides a safe and nurturing space for people to regularly come together to talk about the emotional and psychological aspects of working in health care. The idea comes from work at the Schwartz Centre for Compassionate Care in Boston. What I loved about it, is the recognition of trauma and compassion fatigue for people who work in health care which includes staff like cleaners or kitchen staff who do not get seen as part of the health care team, but often have very intimate conversations and connections with people. I think that having the space to talk about things that matter in the factory system of health care can transform burnout, negativity and cynicism, by providing a sense of community and care and mostly reconnecting people to their purpose in working in health.

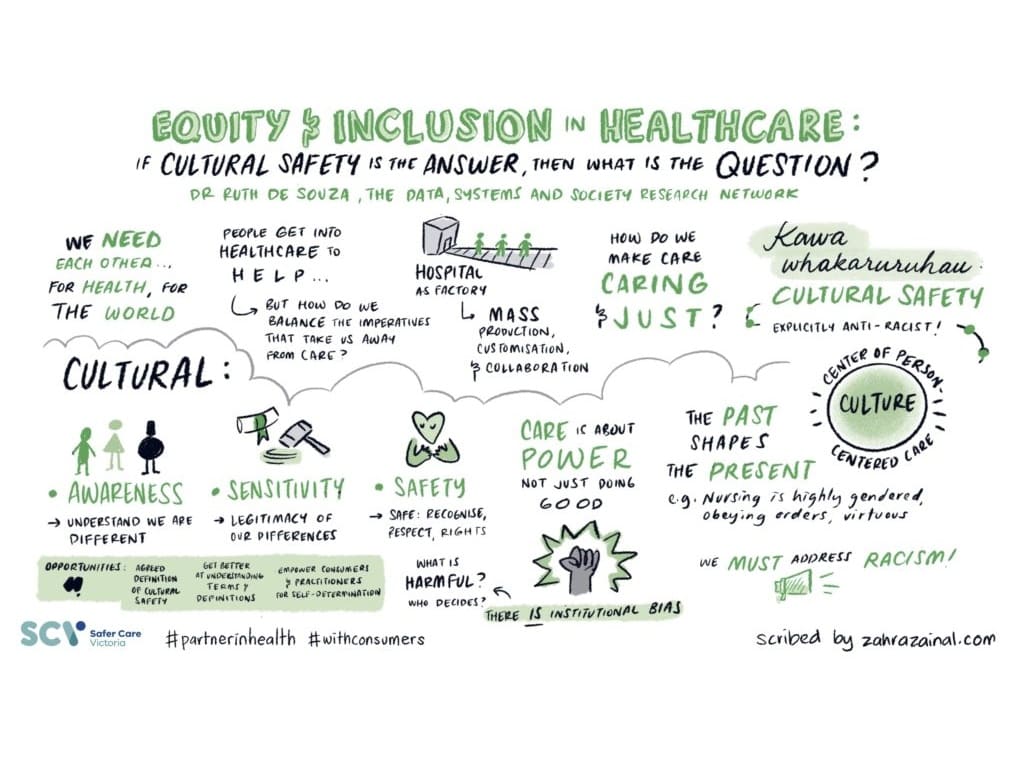

Which brings me to my own presentations at the conference. I did a keynote presentation and a workshop. Rather than attempt to summarise, I’ll leave the last words and images to the most fabulous Zahra Zainal, a Melbourne-based graphic recorder and illustrator, who has so much talent and was able to simplify and amplify my words into stunning illustrations. Please feel share to use and share with appropriate acknowledgement of Zahra and I.

Finally, I’d like to thank the team at Safer Care Victoria especially Lidia Horvath, Belinda MacLeod-Smith, Hayley Hellinger, Louise McKinlay, and Erin Pelly. Also many thanks to sponsors Bang the Table and The Victorian Agency for Health Information.